The Hungarian national uprising began 12 days before Soviet tanks and troops rolled up on the streets of Budapest on November 4, 1956 and crushed the uprising for once and for all. Personal accounts are the stories we tell about our lives that usually portray a larger picture of a life in historical context. Every life has its share of joy and sorrow, victory and tragedy. Personal records, such as diaries can be goldmines of historical research. Diaries as such are documents that beside the unequivocal historical facts enlighten us of remarkable experiences and about the effects of important historical moments on people’s emotions in an intimate way and we are able to relive these moments from their perspective.

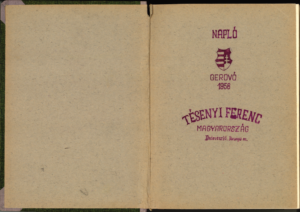

In many ways, diaries and letters are similar: both are archived intimate writings of potential historical value. The following record, the diary of the Hungarian Revolutionary Dr. Ferenc Tésenyi was chosen to be part of the European Digital Treasures second Exhibition ‘Exiles, Migratory flows and Solidarity’.

Can you imagine grabbing a gun as a young pupil to fight for your freedom when a revolution hits in your country?

Well, for the students of the year 1956 in Hungary, when an uprising rose up against communist rule, the life-changing decision to become a fierce freedom fighter was a question of the nation’s life and death. Regarding one man’s impressions of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and its aftermath, the diary of Dr. Ferenc Tésenyi- who was 18 years old at this time – is a very important source. Tésenyi was a student in the city of Pécs and an active member of the revolutionary group called the ‘Invisibles of the Mecsek Mountains’. The ‘Invisibles’ were a group of armed freedom fighters that resisted even weeks after the defeat of the 1956 revolution, hiding in the mountains of the Mecsek Mountain, a mountain range in southern Hungary (Baranya region).

Tésenyi’s account shows us what it was like for the people who lived through the revolution. His entry for October 23, 1956, for example, records how police officers and officials of the State Protection Authority attacked him and other revolutionaries:

‘They were coming step by step, and when they were only 15 steps away from us, they nailed their bayonets at us and started running towards us. They were stabbing and beating with the stock of their rifles those who were standing in the front line, while they were trying to disperse us into the streets opening from the square. But they did it in vain, the people always returned to the square from the other side.’

In the entry for October 25, he notes the jubilation that accompanied the initial revolutionary victories:

‘[…] the red stars fell down from the theatre and the trade union centre, and they were replaced with Hungarian national flags. By this time, we were already about 40,000 people. At the main square, we sang the National Anthem, and then a loudspeaker spoke up: “My fellow Hungarians”, “my fellow citizens!” It was followed by loud applause, and then the police and the State Protection Authority both apologized…’

The ‘Invisibles’, after surviving many Soviet attacks in the mountains – many captured, some of them executed or tortured- had to flee their base. The Soviets were still on their trail, with no chance left, so at the morning briefing on November 16, everyone was acquitted of their oath and then told they had to head west. Finally at dawn, on November 22, some of the ‘Invisibles’ managed to cross the Hungarian-Yugoslav border at Bélavár (town in Somogy County).

Dr. Tésenyi escaped to Yugoslavia where he has been dispatched to Gerovo refugee camp (today a village in Croatia). He later went to high school in the Federal Republic of Germany before enrolling at the medical school of the University of Zurich, Switzerland. He graduated as a dentist in 1965.

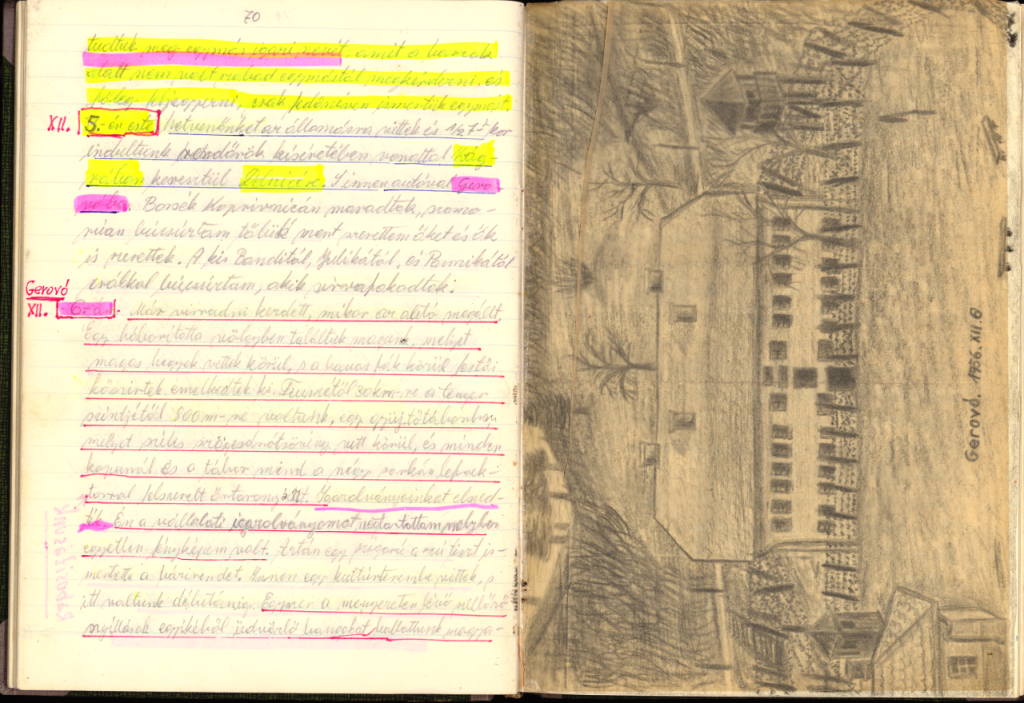

In Tésenyi’s record (a volumed hardback diary on paper, containing 200 numbered pages, 86 pages were written) we can see a pencil drawing depicting the Gerovo refugee camp as it appeared in early December, 1956. At that time the place was surrounded by a double barbed-wire fence, and was overlooked by watchtowers and sentry boxes. It felt more like a Nazi concentration camp than a refugee camp.

In mid-May 1957 the watchtowers and the barbed-wire were removed but the camp still left a lot to be desired. Around 1,400 refugees were packed into buildings designed to hold 600 people. Some families had small rooms to themselves, but most were accommodated in a large common dormitory room along with the others. There was no dining hall at the camp. Some of the refugees made the choice to return to Hungary, others, like Ferenc Tésenyi, stuck it out, and were able to complete the journey to Western Europe or America in order to make a new life for themselves.

Written by Dorottya Szabó, senior archivist,

National Archives of Hungary and

Anna Palcsó, public education officer,

National Archives of Hungary