Yesterday, 25th of November, the second of the three transmedia exhibitions included in the European Digital Treasures project, “Exiles, Migration Flows and Solidarity”, was successfully opened at the Documentary Centre of the Historical Memory (Spain).

Manuel Melgar Camarzana. Director of the Historical Memory Documentary Centre.

María Oliván Avilés. Secretariat General. SG.C.1 – Transparency, Document Management and Access to Documents.

Severiano Hernández Vicente. Deputy Director-General of the State Archives.

María Encarnación Pérez Álvarez. Spanish Government Subdelegate in Salamanca.

This exhibition analyzes how migrations and exchanges have contributed particularly to building cultural diversity in Europe through the documentary treasures kept in European archives. And it is the outcome of the European cooperation, a clear example of the combination of the capacities, heritage, diversity, value, and inspiration of all those who have made this project possible.

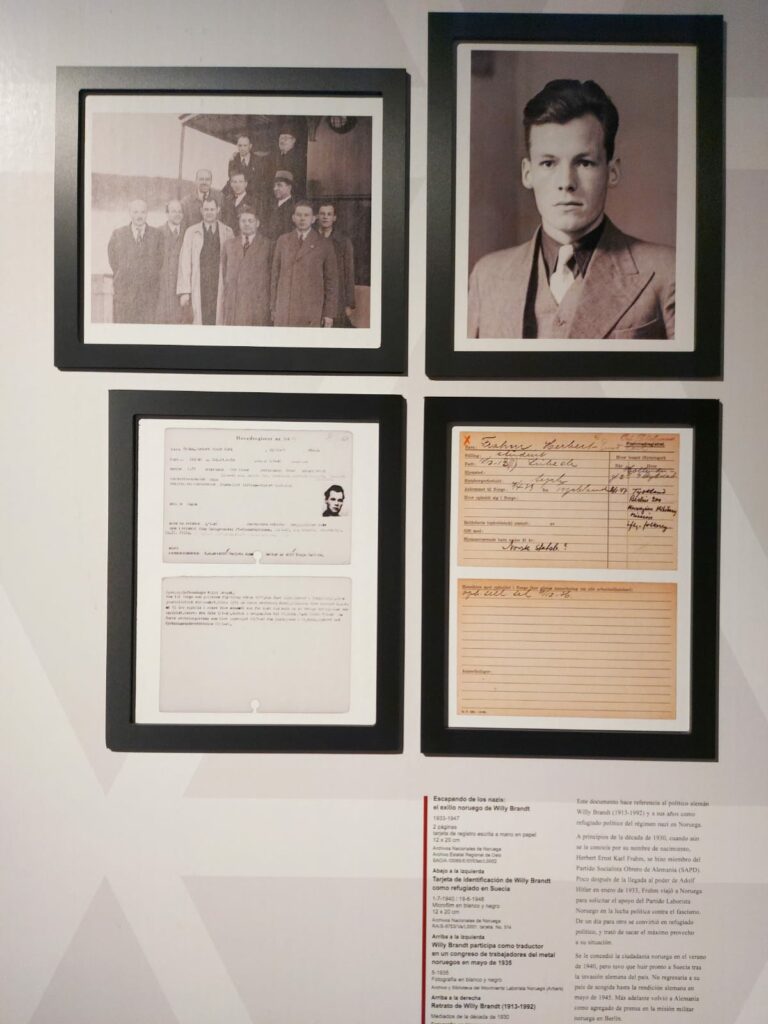

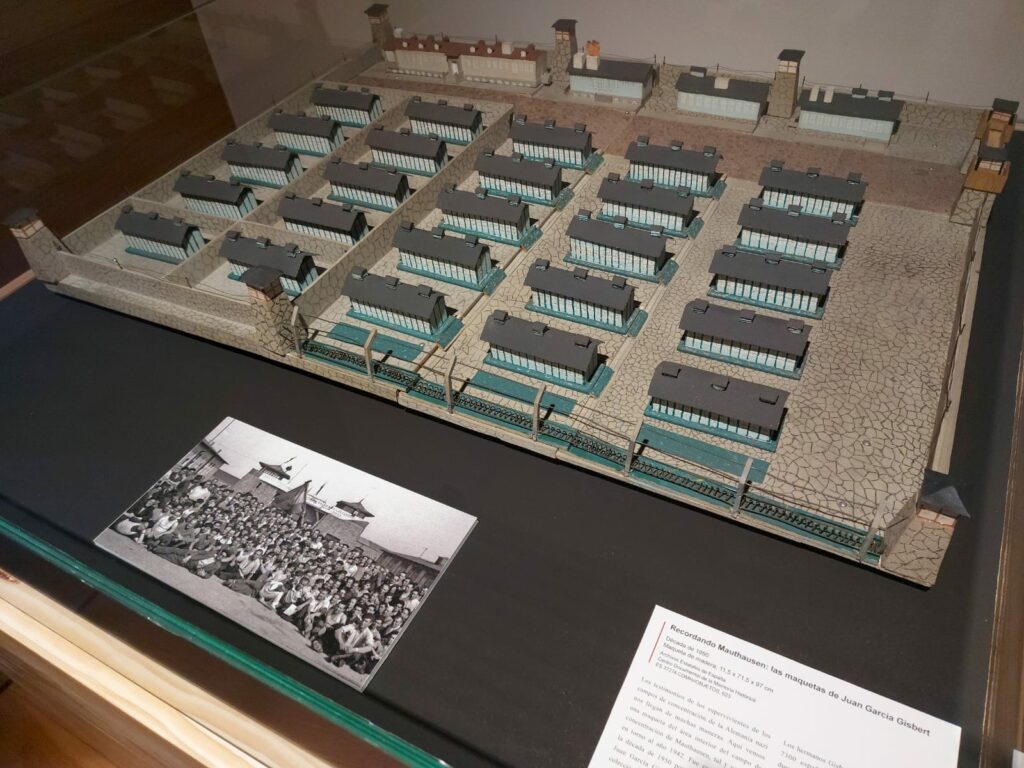

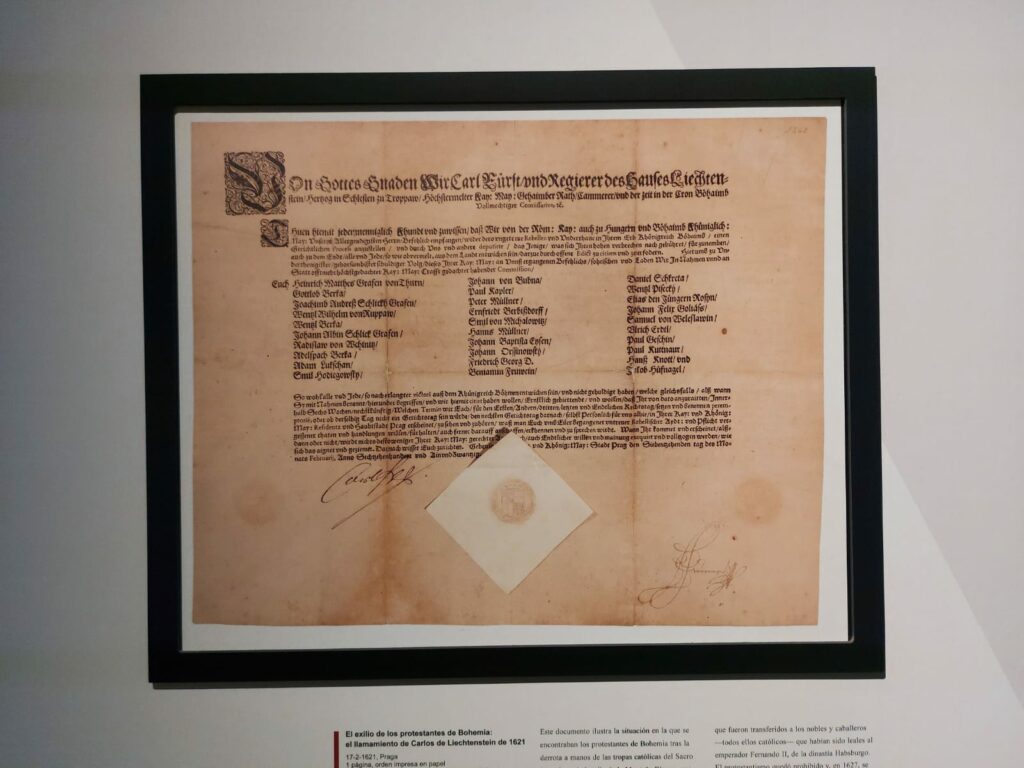

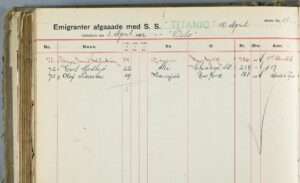

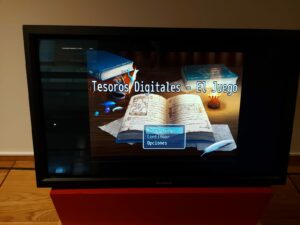

The narratives displayed here combine different technological tools that allow us to get to know our written past through multiple channels. Visitors can interact with: 9 original documents from 4 different archives, 21 facsimiles from 7 countries, 18 digital reproductions of documents from 6 countries, displayed in interactive booths, 1 quiz game for people who love challenges, 1 memory matching game to encourage observation, 1 infinite running game to reward speed by catching archival documents, 1 interactive RPG game to learn how to work on an archive, 4 augmented reality experiences to explore parallel worlds and videos presenting the project and its merchandising products!

Through the selection of 44 documents from the archives that participate in the project, European migrations are narrated from a historical perspective. In a Europe that is currently facing one of its most important migration crises, the relevance of this exhibition is key. The narrative has been structured through three thematic pillars: Work-related Migration; War- related Migration; Political Uprising, Turmoil and Persecution.

The stories combine different tools and technological solutions, with which the public will be able to access the written past through multiple channels that will allow them to experiment, play, learn and share, with that unique ability that documents have to tell personal stories (letters, images, boarding passes, visas, certificates, etc.) behind the European migration figures.

The opening was chaired by Severiano Hernández Vicente, Head of the Spanish State Archives, by María Oliván, Head of the Transparency, Document Management & Access to Documents Unit of the European Commissio, by Manuel Melgar, Director of the Documentary Centre of the Historical Memory, and by María Encarnación Pérez Álvarez, Government Sub-delegate in Salamanca. It was also attended by representatives of the University of Salamanca, of different archives of the province of Salamanca, by the members of the ‘European Digital Treasures’ project and a representation of the Spanish State Archives.

The exhibition can be visited until March 13th, 2022 in Spain, with capacity restrictions and hygiene and safety measures established by health authorities to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Practical information: https://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/cultura/areas/archivos/mc/archivos/cdmh/portada.html

Written by Spanish State Archives.