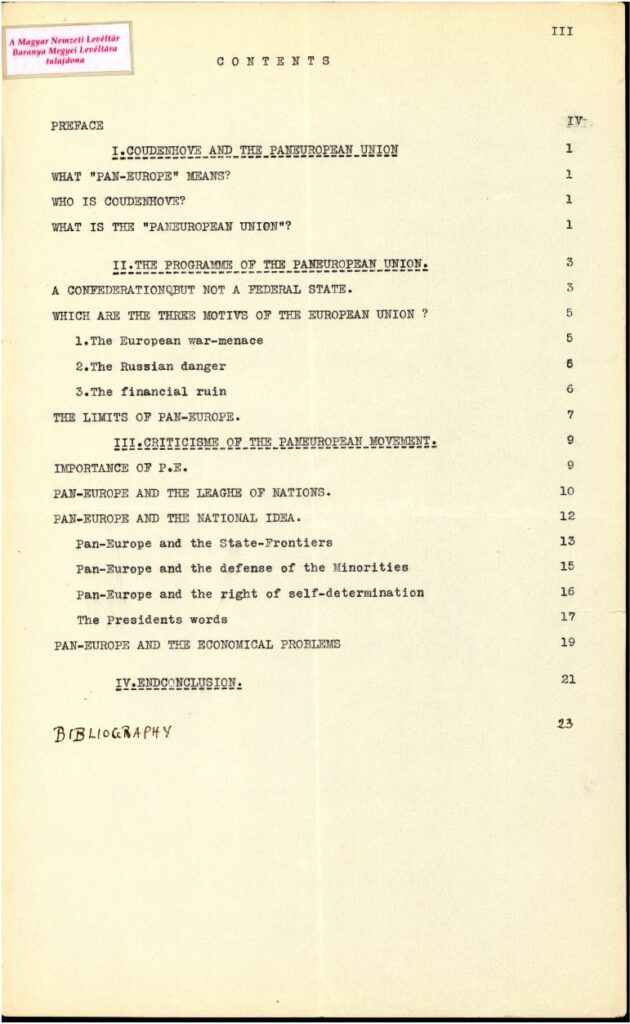

The following document is the March 18, 1928 issue of the Pan-European Movement’s Hungarian-language periodical, the Pan-European Bulletin, written in English language. It was edited by the Hungarian Ferenc Faluhelyi (October 29, 1886 – December 24, 1944), an international law expert and founder of the Institute of Minorities of the University of Pécs. This record will be on display at the first thematic exhibition of the European Digital Treasures project, entitled Construction of Europe – History, Memory and Myth of Europeanness over 1000 years. You can read more about the exhibitions here.

Over the years, the interests of Ferenc Faluhelyi gradually aimed from public and criminal law to international law – which he consistently mentioned as interstate law in his lectures and studies. As a researcher and professor, he had been concerned with minority issues since 1926, proclaiming the principle of the equality of states and, within this, the need for the citizens of individual nations to exercise their fundamental rights. He considered the issue of minority protection as a point of doing.

The Hungarian Pan-European Committee was established in Budapest on June 24th, 1926. Lawyers, economists, and representatives of the economic and financial circles played a prominent role in establishing and promoting the goals of the movement. The pursuit of the Hungarian committee – similarly to the government’s foreign policy – started from the injustice of the peace treaty and fought for its revision.

The Pan-European Movement was an appropriate answer to the issue of the national minorities, since its main feature was the aspiration to reduce the significance of the state borders. A united Europe was important for them, because the continent could only defend itself from the threats of the Soviet Union by the power of unity. The idea was to bring the Pan-European Movement closer to the customs union, with unconditional respect for minority rights, language and cultural development, and free contact between minorities in other parts of the country, especially with their “blood brothers in the motherland”.

Hungarian Pan-Europeanists considered it important to clarify their relationship with the nation and to define the relationship between the European and national elements. Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi believed that the feeling of belonging to a nation – like the religion – could be a private matter, and thus the concept of a European nation could be formed. Hungarian Pan-Europeanists did not accept this position, rejected it, considered it a utopia to strive for uniformity, and saw the uniqueness and strength of a united Europe in the totality, harmonious coexistence and cooperation of individual cultures represented and mediated by different nations.

The Pan-European Movement also attracted significant personalities in Hungary, but was unable to put pressure on government circles that did not recognise – or did not want to recognise – the forum provided by the Pan-European Movement to promote foreign policy goals and seek allies. The Hungarian government, like other European governments, did not want to achieve its foreign policy goals by coordinating them with the interests of other states, in a Pan-European framework, but by balancing them between states, taking advantage of their contradictions. The possible development of the Pan-European orientation of the government – as in the case of the other states – could have been greatly helped by the official establishment of the Franco-German rapprochement and cooperation. By the time the Briand Plan based on this could have been discussed, the economic situation was no longer appropriate and the Pan-European political environment was becoming less and less appropriate.

The achievements of Ferenc Faluhelyi in the field of protection of the minorities were honored in 1933 by the Hague-based Association Internationale Pour les Études du Droit des Minorités, and in that year he was awarded the Badge of the Order of the Crown of Italy for his distinguished knowledge and presentation of Italian international law.

Anna Palcsó

Public Education Officer, National Archives of Hungary